About 100 groundwater conservation districts across Texas monitor and plan the use of a resource we can’t see – groundwater.

These districts rely on data and computer modeling simulations to help them predict how much water remains in groundwater aquifers, balanced against projected needs, to determine how groundwater should be managed.

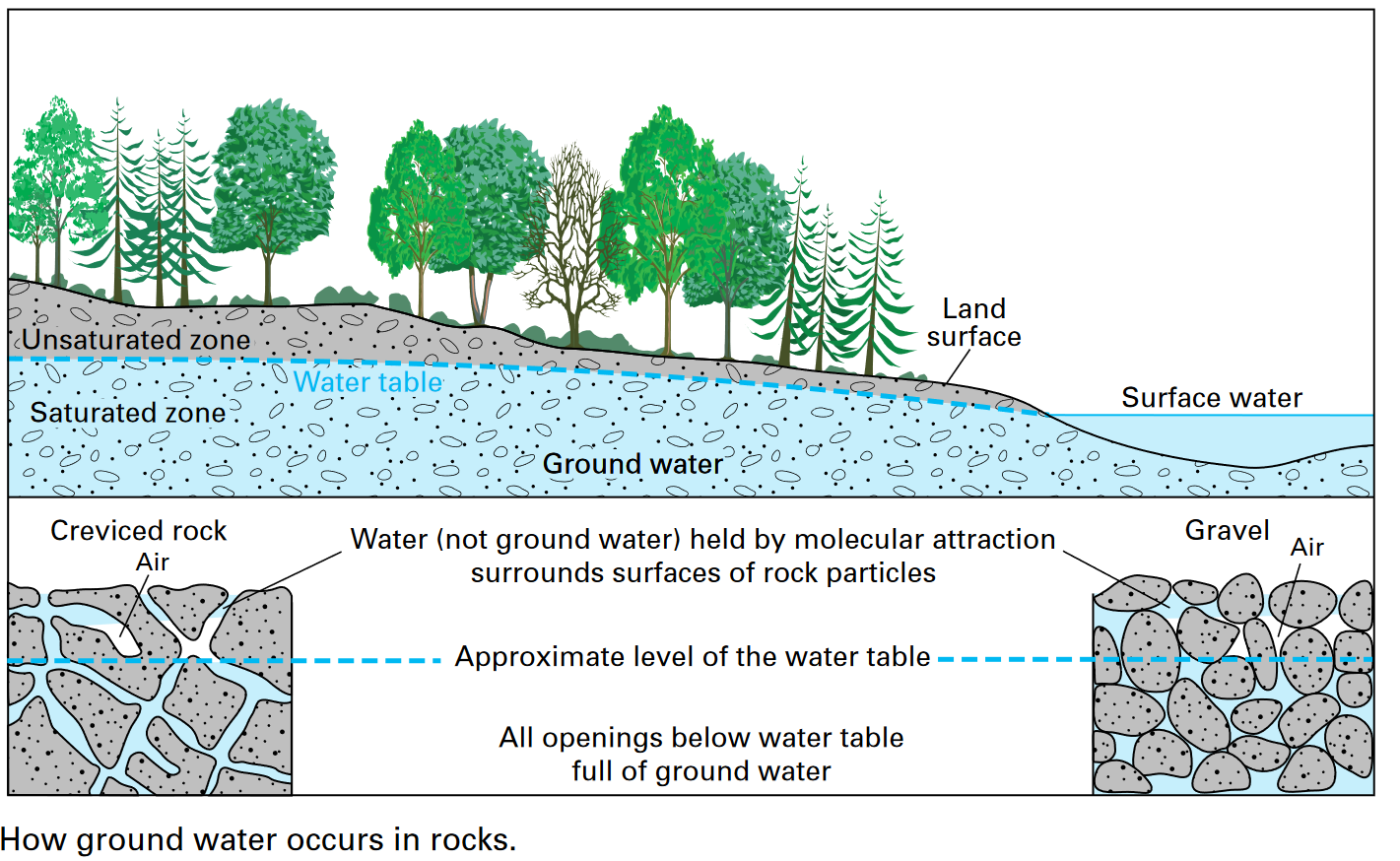

Having trouble visualizing groundwater? This explanation from the U.S. Geological Survey should help.

From the USGS Water Science School:

Some people believe that groundwater collects in underground lakes or flows in underground rivers. In fact, groundwater is simply the subsurface water that fully saturates – or fills — all the pores or cracks in soils and rocks

Groundwater is replenished by precipitation and, depending on the local climate and geology, is unevenly distributed in both quantity and quality. When rain falls or snow melts, some of the water evaporates, some is transpired by plants (think of a plant exhaling water vapor), some flows overland and collects in streams, and some infiltrates into the pores or cracks of the soil and rocks.

The first water that enters the soil replaces water that has been evaporated or used by plants during a preceding dry period.

Between the land surface and the aquifer water is a zone that hydrologists call the unsaturated zone. In this unsaturated zone, there usually is at least a little water, mostly in smaller openings of the soil and rock. The larger openings usually contain air instead of water.

Molecular attraction holds water in the unsaturated zone, surrounding the rock particle surfaces. Similar forces hold enough water in a wet towel to make it feel damp after it has stopped dripping. The water in the unsaturated zone will not flow toward or enter a well.

Some water gets down to the saturated zone to an aquifer. All the spaces between the rock particles are filled with water, which will flow toward a well because it is under pressure.